Following the suicide cases reported in Andhra Pradesh on account of recovery tactics adopted by MFIs, there have been several articles in the press debating the pros and cons of “regulating” interest rates that can be charged by MFIs to their clients. The present average of about 40% charged by MFIs is considered “usurious” and there seems to be a general consensus (by those in favour of regulation) that a ceiling rate of 24% is necessary so that MFIs meet their social objectives.

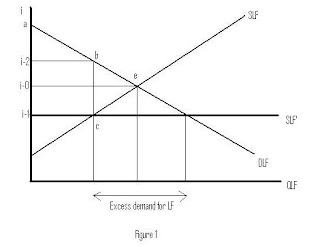

The economic implications of regulating interest rates charged by MFIs can be studied using a simple demand-supply framework. In Figure 1 we consider the MFI market for loanable funds where DLF and SLF are the demand for and supply of loanable funds respectively. Without regulation, the free market equilibrium interest rate is i-0. If a ceiling rate is enforced at (say) i-1, then we will have an excess demand for loanable funds. Simple economic theory tells us that at this rate, some MFI may not able to meet their costs and may exit from the market or they may not be able to provide credit in some locations or regions on account of higher operating costs there. Whatever, the reasons, there is an overall loss of welfare although it is possible (though not necessary) that some clients may actually gain in terms of higher consumer surplus (i.e. the difference between what they pay and are willing to pay, the latter based on the “profitability” from putting their loans to use). In Figure 1 consumer surplus changes from i-0ae to abci-1.

But is this the final outcome? Once again elementary microeconomic analysis tells us that this may not be the case. Since an excess demand for loanable funds exists at i-1, some sort of rationing may well arise so that the effective rate charged to clients may actually be i-2. The MFI, if they know the clients willingness to pay, could charge this higher rate to their clients, perhaps unofficially. Some kind of “black market” could develop. Even at the interest rates of 36-40% charged presently, there are some reports of the actual rates paid by clients being in the range of 60%. If this happens, producer surplus could increase but borrowers would definitely find a decline in consumer surplus from i-0ae to abi-2.

The proponents of regulation seem to base their argument on the supply of loanable funds curve being perfectly elastic as in Figure 2. A ceiling on interest rates from i-0 to i-1 moves the supply curve from SLF-0 to SLF-1. Consumer surplus increases from i-0ae-0 to i-1ae-1. The question is how does a perfectly elastic supply curve actually shift? As Ananth and Mor (Mint, Nov 2, 2010) point out, “the only way out is to aggressively promote competition between entities and facilitate entry of disruptive new models”. But here again there is a danger of the Jevons Paradox taking effect: the lower interest rate actually ends up with clients reeling under excessive debt burden (i.e. the quantum of debt increases from Q0 to Q1 in Figure 2).

Ananth and Mor, however, think that this may not actually happen in India as compared with countries like South Korea

This brings to another important observation that needs further study. We all know that at the core of microfinance, both through MFIs and SHGs, is the group. Lending to a group ensures almost zero percent default. But consider this argument: what happens to a person who cannot repay a loan? Can the peer pressure of a group (usually of the same caste and community) push a potential defaulter to more extreme steps? Losing face with a person from your own community could be even worse than defaulting payment to a moneylender; in the latter case perhaps members of your community would at least sympathize with you. This of course is only a hypothesis, not a claim.