You can find my latest paper publsihed in Global Environment at this link.

http://www.globalenvironment.it/sivramkrishna.pdf

Here is the abstract of my paper:

Macroeconomic and Environmental History: The Impact of Currency Depreciation on forests in British India, 1873-1893

The impact of the macroeconomic context, particularly monetary disturbances, on the environment has been hitherto ignored in the study of Indian environmental history. Th e links between macroeconomics and the environment, however, have been extensively studied and debated in recent times in connection with the structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) that many developing countries have been induced to adopt. A closer examination of India’s monetary history reveals that there exist many similarities between the effects of SAPs and those of monetary disturbances in the last quarter of the nineteenth century due to the depreciation of the rupee. Th is paper traces out how an exogenously induced change in the macroeconomic environment may have led to policies that prompted increased deforestation. Moreover, in the private sector too the depreciation of rupee may have led to higher levels of investment and exports of environmentally sensitive products, further accentuating the adverse impact on forests. Although not conclusive in quantitative terms, this study nonetheless attempts to show that colonial policies cannot be studied from a purely ideological, political, or real-economic point of view; the macroeconomy, particularly monetary variables that were sometimes beyond control of governments, may also have induced changes in deforestation rates.

Sunday, November 28, 2010

Thursday, November 18, 2010

Too much of the better may be for the worse

The move towards banning the incandescent bulb and replacing it with the compact fluorescent lamp (CFL) is getting stronger across the world. The CFL is far more energy efficient than the bulb using 20 to 33 percent of the power of equivalent incandescent bulb. The cost efficiency of CFLs, however, remains in doubt. But studies claim that in spite of higher initial costs, the extended lifetime and lower energy consumption of CFLs make it cost efficient too. The savings are more for commercial establishments where usage is greater. Moreover, when aspects like cooling costs and manpower requirements for the change of bulbs are considered, the CFL comes out a clear winner. The superior resource and cost efficiency of CFLs has by and large come to be widely accepted throughout the world.

The benefits to society that arise from the resource efficiency of CFLs are many: cost savings at the micro level, lower utilization of fossil fuels for electric lighting thereby reducing green house gas emissions, and where power is generated from hydroelectric plants, saving of water resources and reduced need for building new plants that impact forests and ecosystems. Such positive externalities in containing environmental damage with the use of CFLs has even warranted governments to consider subsidies or utilization of carbon credit schemes to lower the initial investment of switching over from bulbs to CFLs. Will the CFL then bring in a greener future? One nineteenth century economist, William Stanley Jevons would have given an unexpected answer; no.

Jevons (1835-1882) is best known for his seminal work, The Theory of Political Economy (1871). But his recognition as an economist had come with the publication of The Coal Question (1865) in which he made a remark that has now come to be known as the Jevons Paradox,

It is wholly a confusion of ideas to suppose that the economical use of fuel is equivalent to a diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth.

His explanation of the paradox was simple: physical resource efficiency implies lower costs and prices, stimulating demand that more than compensates the initial savings in the use of a resource like coal. It is important to understand that the paradox articulated by Jevons should not be taken as an anti-resource efficiency stance. There is no doubt that resource efficiency unequivocally benefits society. However, what the paradox makes us conscious of is the error to suppose that resource efficiency will lower overall consumption of that resource. It is this latter point that is especially critical in the context of policy formulation for environmentally sustainable development.

The Jevons Paradox can be extended to CFLs. If ultimately CFLs means cheaper lighting then a lot more of it will be demanded so that the need for power may well be more than was the case when expensive bulbs were the only option available. The increased quantum of lighting possible with CFLs is no doubt beneficial to society but what cannot be inferred is that this is also a solution to environmental concerns; in fact, the dilemma of development versus the environment might only deepen. The question that must then be asked is how are we to prevent the negative impact of resource efficiency from taking effect or even better, make sure that resource efficiency will generate a positive outcome? One option is to ensure that resource efficiency is accompanied by conservation. This, economists argue, requires a tax to be levied on the (efficient) resource rather than encouraging its extensive use through subsidies. With CFLs, their high initial costs might in fact serve as a kind of tax. But there is a concern that poor households may not be able to bear such high fixed cost and it is, therefore, necessary to subsidize CFLs. If the subsidy on CFLs is universal (available to all consumers) then the Jevons Paradox will take effect; subsidizing efficient resources to encourage their extensive use in order to address environmental issues becomes self-defeating. If, on the other hand, subsidies are targeted towards poor households only, there is a danger of re-sale of subsidized lamps in the grey market so that these households use even less lighting than before (à la Jevons Paradox). Policy formulation ignoring Jevons Paradox is fraught with danger of arriving at such unanticipated and unfavourable outcomes.

Like CFLs, there are many similar instances where Jevons Paradox might result in unexpected outcomes, both positive and negative. Positive examples including lower tax rates that beget higher net collections or new technologies which throw people out of work but eventually benefits labour because the additional demand for cheapened products. The introduction of computers into offices in the 1990s is a case in point. Instances where “resource efficiency” ends up generating unexpected adverse outcomes are even more common. Low-cal foods, lax diet control and increased food consumption that ends up in greater calorie intake; energy efficient air-conditioners prompts longer hours of use; fuel efficient vehicles to conserve petroleum that actually encourage more (wasteful) usage, microfinance to lower rural indebtedness but instead promotes greater profligacy, faster downloading speed that entices us to spend longer hours on the Net, organic foods that increase demand for dung and cattle grazing, spawning deforestation … the list where Jevons Paradox takes effect is endless. But in the Foreword to the book, The Myth of Resource Efficiency, Joseph A. Taitner suggests an even more interesting approach to its study with the question, “where is the Jevons Paradox not in effect?”

Wednesday, November 3, 2010

Interest Rate Ceiling on MFIs: Some Implications

Following the suicide cases reported in Andhra Pradesh on account of recovery tactics adopted by MFIs, there have been several articles in the press debating the pros and cons of “regulating” interest rates that can be charged by MFIs to their clients. The present average of about 40% charged by MFIs is considered “usurious” and there seems to be a general consensus (by those in favour of regulation) that a ceiling rate of 24% is necessary so that MFIs meet their social objectives.

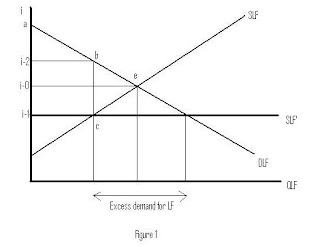

The economic implications of regulating interest rates charged by MFIs can be studied using a simple demand-supply framework. In Figure 1 we consider the MFI market for loanable funds where DLF and SLF are the demand for and supply of loanable funds respectively. Without regulation, the free market equilibrium interest rate is i-0. If a ceiling rate is enforced at (say) i-1, then we will have an excess demand for loanable funds. Simple economic theory tells us that at this rate, some MFI may not able to meet their costs and may exit from the market or they may not be able to provide credit in some locations or regions on account of higher operating costs there. Whatever, the reasons, there is an overall loss of welfare although it is possible (though not necessary) that some clients may actually gain in terms of higher consumer surplus (i.e. the difference between what they pay and are willing to pay, the latter based on the “profitability” from putting their loans to use). In Figure 1 consumer surplus changes from i-0ae to abci-1.

But is this the final outcome? Once again elementary microeconomic analysis tells us that this may not be the case. Since an excess demand for loanable funds exists at i-1, some sort of rationing may well arise so that the effective rate charged to clients may actually be i-2. The MFI, if they know the clients willingness to pay, could charge this higher rate to their clients, perhaps unofficially. Some kind of “black market” could develop. Even at the interest rates of 36-40% charged presently, there are some reports of the actual rates paid by clients being in the range of 60%. If this happens, producer surplus could increase but borrowers would definitely find a decline in consumer surplus from i-0ae to abi-2.

The proponents of regulation seem to base their argument on the supply of loanable funds curve being perfectly elastic as in Figure 2. A ceiling on interest rates from i-0 to i-1 moves the supply curve from SLF-0 to SLF-1. Consumer surplus increases from i-0ae-0 to i-1ae-1. The question is how does a perfectly elastic supply curve actually shift? As Ananth and Mor (Mint, Nov 2, 2010) point out, “the only way out is to aggressively promote competition between entities and facilitate entry of disruptive new models”. But here again there is a danger of the Jevons Paradox taking effect: the lower interest rate actually ends up with clients reeling under excessive debt burden (i.e. the quantum of debt increases from Q0 to Q1 in Figure 2).

Ananth and Mor, however, think that this may not actually happen in India as compared with countries like South Korea

This brings to another important observation that needs further study. We all know that at the core of microfinance, both through MFIs and SHGs, is the group. Lending to a group ensures almost zero percent default. But consider this argument: what happens to a person who cannot repay a loan? Can the peer pressure of a group (usually of the same caste and community) push a potential defaulter to more extreme steps? Losing face with a person from your own community could be even worse than defaulting payment to a moneylender; in the latter case perhaps members of your community would at least sympathize with you. This of course is only a hypothesis, not a claim.

Monday, November 1, 2010

A Note on Foreign Currency Reserves

In today’s context of exchange rate instability and the currency wars there is an urgent need to address the problem of “reserves” that many countries have piled up over the last decade or two.

This note presents the simple economics of foreign currency reserves. I begin with what I call the expanded balance of payments equation:

X – M = + R – (F + H + B) ………………. (1)

Where X = exports; M = imports; R = reserves; F = FDI inflow; H = portfolio investment inflow and B = net borrowings (inflow). Note that outflows of F, H and B would mean a negative quantity. Suppose the country has a surplus in current account of $100 (X – M = 100), then if R = 0, we must have F + H + B as -100 so that X – M = 100 = 0 – (-100) = 100.

Now consider the situation where F = H = B = 0, then X – M = R. In this case if R = 0, then X – M = 0 or X = M. Let $ (USD) be the foreign currency and Rs. (Rupee) the domestic currency. What this means is that if a country does not hold foreign currency reserves, then we must have current account balance, ceteris paribus. Figure 1 clearly shows what happens when a country is at equilibrium at E0 followed by a shift in its supply of foreign currency curve (S$) curve. In this case, the excess supply of foreign currency will mean that the domestic currency (Rs. = rupees) appreciates till we reach point E1 where S$’ = D$.

To prevent the appreciation in currency and the subsequent loss in exports as we move from E00 to E1, the central bank could intervene in the forex market by buying dollars at the initial exchange rate, er0. The dollars purchased by the central bank are what we call as “reserves” or R in equation (1) above. Whatever the purpose of a country holding reserves of dollars may be, it is clear that reserves would lead to a depreciation of the domestic currency (Rs.) vis-à-vis the dollar ($). There is extensive literature on why countries hold reserves and what is the optimum amount of reserves that a country should hold; whether reserves are held based as part of a mercantilist strategy or to protect themselves against forex market turbulence or as an insurance against financial risks. In addition to the why it is nonetheless important to understand the implications of holding reserves. It is also clear from Figure 1 above, that when the domestic country holds reserves, from equation (1) it is clear that X > M or X – M > 0. If so, in a two-country model, we must have M > X or a current account deficit for the USA. Simple as this may seem, many people begin with the USA running large current account deficits as the basis of attack against its economic policy. However, failure to consider the implications of its trading partners holding high volumes of reserves, render such arguments incomplete.

Now consider a situation where there are capital inflows into the domestic economy (assume B = 0). Let A = autonomous transactions in the balance of payments where:

A = (X – M) + F + H ……………….. (2)

These would then give us the S$ curve. If we consider R as the only accommodating transaction (on the balance of payments) which gives us the D$ curve, then in Figure 2 we can see how the central bank can manipulate the exchange rate by “choosing” an appropriate level of R.

In Figure 2, with an increase in hot money inflows, A shifts to A’. To maintain the exchange rate at er0, the central bank must increase its reserves from R to R’. Reserves then become the instrument to control the exchange rate.

But there are consequences for the domestic economy on account of increasing reserves. When the central bank buys $s, it injects rupees into the economy. This, as we know, shifts the LM curve outwards, reduces interest rates, increases output. However, from the AS-AD framework we also know that a shift in LM curve implies a shift in the AD curve. The higher output comes at the cost of higher inflation.

We have so far considered a two country model. If we extend the model to include more than country, say, the EU, we could have more than one reserve currency, say, euros (E) and dollars ($), i.e. RE and R$. We could also include gold (G) as a component of reserves along with SDRs (S). The balance of payments equation will then be:

X – M + F + H + B = R$ + RE + S + G ……………. (3)

It is clear from equation (3) above that an increase in G may not have an impact on the Rs./$ exchange rate. If, for example, the gold is bought from Australia

Consequently, we propose the following hypotheses for further empirical study: countries, especially those which intend to stimulate growth through exports and foreign investment (like China or India

This brief note also throws light in the question we raised earlier. Why does Europe hold a large percentage of its reserves in gold and countries like China and India

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)